Take a trip down memory lane with us. Re-discover stories and reflections that we've captured over the last years. This article was first published in 2018 and, yet, is more relevant than ever.

What do we mean by the ‘gendered nature’ of urban space? How can a better awareness of gender create safer and more inclusive cities?

These questions were explored back in the very first URBACT Gender Equal Cities workshop in Stockholm (SE), back in 2018. The session took place within the framework of the inaugural European Placemaking Conference. Over 2 days 170 participants from 20 countries came together to consider how cities, civil society and professionals can meet the challenges of displacement and loss of affordability in urban centres across Europe. How can we as placemakers strengthen spatial justice, to build the cities for all, aspired to in Sustainable Development Goal 11? The call to action, in line with URBACT’s mission, was to be aware of the bigger picture: to understand the political, cultural and economic dynamics of the city and to boost cohesion by involving all communities, stakeholders and voices in a meaningful way.

Gender Equal Cities, URBACT’s new initiative, seeks to highlight ways in which cities are driving change to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 5: Gender Equality. As this was the first ever consultation for us specifically on this topic, we were keen to get the ball rolling and start the debate. Through presentations and discussion a number of strong messages emerged.

- Involve women and girls more in every stage of urban design

- Pay more attention to all women’s voices to ensure we feel relaxed and safe in public spaces

- Plug the knowledge gap on what makes public space more inclusive, what girls and women want

- Collect, analyse and use disaggregated data about public space relating not only to gender, but age, ethnicity, disability, class

- Understand how to integrate both women friendly spaces and women only spaces

- Adapt participatory methods to be welcoming and appropriate

The Gendered City

To begin with, Linda Gustafsson, Gender Equality Officer, presented the URBACT Good Practice on gender mainstreaming in Umea, northern Sweden, where the city has committed to involving all citizens in co-creation. She stressed that:

“A sustainable city can only be built together with those who will live in it. All planning should be permeated by openness, democracy and equality. We will develop the city and the public space so that everyone, women and men, children, young people and people with disability, can participate on equal terms. That leads to a city for everyone.”

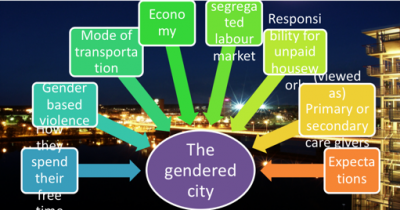

Crucially, Linda also explained the factors that contribute to how the city is experienced in a gendered way, which include the segregated labour market, modes of transport, different ways of moving around, gender based violence, responsibility for unpaid labour and caregiving, and use of free time.

In order for policymakers to understand these differences in the way women and men experience the urban environment we need more training, awareness and better evidence of the specific challenges faced by women and marginalised groups.

Cornelis Uittenbogaard of the Safer Sweden Foundation presented research results on perceptions and reality in relation to the key issue of safety.

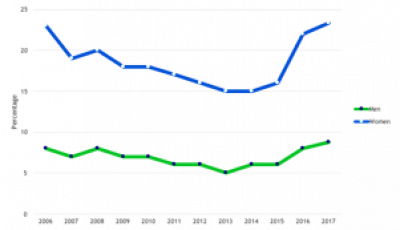

Even in a country like Sweden, seen as a beacon for equality, public space is not perceived equally between men and women. Fear of being a victim is generally 10-15 percentage points higher in women than men and 50% of women reported feeling unsafe in ‘vulnerable areas’. Gendered violence doesn’t just affect women: the reality is that men are in fact more often victims of violence and robbery in public space, but women are 540% more often victims of sexual abuse. One explanation for these differences is how women’s internalised fears affect their perceptions of and behaviour within public spaces.

The analysis from both Cornelis and Linda was that many inequalities stem from the fact that public space is often dominated and designed by men: it may not be accessible for all, it lacks the right kind of street life and effective lighting. The simple solution- easier said than done- is to plan a good city, which includes a flow of activity, a mix of functions and the vibrancy born of daily interactions.

The examples and views shared by participants, reported below, help us move in the right direction.

Feminist Urban Planning

In Sweden the concept of feminist urban planning is rapidly growing into mainstream practice. One element of Umea’s gender equality strategy is a bus tour which shows visitors and citizens around the city and invites them to look at it afresh from a gender perspective. They consider for instance how the sports facilities are used, who uses public transport, where the parking spaces are in relation to employment hubs and the hospital, as well as which parts of the city look uninviting and poorly lit. This tour serves both as an awareness raising tool, and a means to develop better policy and practice through regular revisiting of the gendered city.

In Husby, Sweden, an initiative was started by local women who felt unsafe and saw public places were dominated and controlled by men. Svenska Bostäder, a housing company owned by the city of Stockholm, developed the central area from a feminist perspective. The new measures include social activities welcoming to women, lighting, access to the metro, a new café to replace one that was only frequented by men, a playground, more commerce and a market.

Universal Design, spaces for all and spaces for women

The principles of good planning and universal design, taught in most urban disciplines, but maybe not with sufficient emphasis or resonance, can help to create places that are well-loved and well used by people of all walks of life, of a mix of ages, genders, religions, socio-economic classes and ethnicities. Jacqueline Bleicher of Global Urban Design reminded us "In a truly inclusive, universal place women feel safe, children run and play, the elderly can sit and socialise, teenagers can chat with friends, and singles can read in comfort. Everyone can be their best self, feel comfortable and be at peace with their neighbour." So keeping these principles central to the process can help create more gender sensitive places.

Minouche Besters of STIPO talked about the need to have different types of spaces in the city for inclusion generally, and gave examples from the Netherlands. A ‘one size fits all’ approach is an activity or space designed to make sure that it is accessible for all, such as Debuurt park camping: low cost, local, with the facility to rent equipment and no alcohol on sale to respect cultural values. The ‘special size for special fit’ are more customised, single sex initiatives aimed at creating a feeling of security and confidence. An example was the swimming pools that have specific women only times, when girls and women can happily swim in burkinis.

Intersectionality

This led us to the question: ‘How can the needs of women whose voices may be marginalised, who are experiencing multiple forms of discrimination be amplified and brought into the design and animation of public space? Examples were shared of initiatives that harnessed the entrepreneurial drive of migrant women and pride in their culture.

Rozina Spinnoy, Director of BIDS Belgium reported on a project in Brussels established with Turkish women who wanted to run a Festival in her local park. The Flemish Government helped facilitate crowdfunding of 17,000 Euro to create a local community Summer cafe/bar for social and cultural gatherings, encouraging inclusive activities with entrepreneurial women from Moroccan, Turkish and many other origins. These events encourage a feeling of ‘safety’ as well as inclusivity, with activities running in late Summer evenings in the public spaces around the cafe. In Denmark, local Latin American women set up a neighbourhood movie club, in part driven by their desire to make sure their children knew their roots. Involving marginalised women has to be meaningful and bring benefit for them, which can also include better access to local authority staff and services.

Knowledge Gap

The absence of women and girls in the urban planning process creates a knowledge gap, resulting in public spaces that exclude. White Architect’s Places for Girls research project undertook the mission to find out how to create better places for girls in the city. Designed as an art project, a multi-disciplinary team – including girls from a Stockholm youth council – collaborated to answer questions around identity and equity. A concrete example of the outcome was that the young women consulted stated a clear preference for public seating in formations opposite each other, rather than the usual single bench looking out in one direction asserting: “We want to look each other in the eye.”

Participatory processes

Above all, better participatory dialogue and processes hold the key to more inclusive design. Rebecca Rubin of White Architect’s reported how they had learnt from the girls who came into their studio how they preferred to work collaboratively, not competitively. The teenage girls become the experts, the professionals had their assumptions challenged and the co-design methods were improved as a result.

Amplifying the conversation

This first URBACT Gender Equal cities workshop concluded with the resounding consensus that education and awareness are vital. In particular there is a need to take the conversation about gender sensitive planning into traditionally male-dominated environments such as real estate, transport companies and architecture, for women to be change agents alongside male allies. Our goal is to bring together local stakeholders and women's voices, not just once, but over the long-term to create the awareness that can lead to better designed, gender equal cities. The vision of a gender equal city is everyone’s responsibility, and in everyone’s interest. When we strive for great places, with a heightened awareness of gender specific needs and the tools to include and co-design for all, we can start to make a difference.