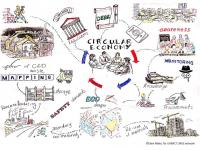

Cities can be pioneers in the path towards the circular economy through the creation and demonstration of new business models.

In this article, I present some urgent actions that cities can adopt and questions they need to address to better manage and conserve resources.

The article is inspired by the first insights coming from the work of the URBACT Action Planning Network URGE: Building circular cities, led by the City of Utrecht.

The article aims to show how cities can become better prepared to fulfil their role as major contributors to the achievement of EU sustainability goals and pave the way for the implementation of the European Green Deal.

A new political impetus

In March 2020, the ‘New Action Plan on Circular Economy for a Cleaner and more Competitive Europe’ was launched by the European Commission. This introduces a strong and coherent policy framework that will foster sustainable products, services and business models. It envisages to establish new consumption patterns so that no waste is produced in the first place.

This policy framework identifies key product value chains that should be addressed as a matter of priority. These include: ICT and electronics; batteries and vehicles; food, water and nutrients; packaging; plastics; textiles; and buildings and city infrastructure.

Through this new policy framework, the Commission is inviting EU institutions and bodies to actively contribute to the implementation of the circular economy. It is also encouraging Member States to adopt or update their national circular economy strategies, plans and measures in the light of the overall ambition.

This is also an area in which cities have a key role to play, not least in designing, testing and applying circular principles on the ground. Most importantly, they need to develop strategies and policies towards integrated sectorial approaches.

The importance of new markets

City-level strategies need to address current waste management practices, including the imposition of measures to foster the local exploitation and re-use of materials from certain waste streams as ‘secondary raw materials’ (SRM).

However, this cannot be done if relevant technical standards are not in place to ensure SRMs’ performance and safety. In parallel, further actions are needed at operational level to prepare the ground towards the wide use of SRM, including the introduction of incentives for rewarding improved sustainability performance.

Cities must also be prepared to assess the feasibility of establishing a market observatory for key SRM, map the flows of materials and enable information exchange between SRM sellers and potential buyers. Thus, new business models will evolve, impacting positively on the creation of new jobs and improved human capacities.

Strategies need to start with the implementation of such practices in public procurement, given the fact that public authorities’ purchasing power represents 14% of EU GDP, according to the European Green Public Procurement Criteria and Good practices. Influencing and adopting legislation towards the increased use of SRM will be critical.

Without forgetting the human angle

For new business models to be successful, it is essential to boost demand; actions to increase awareness of citizens are essential. Increased demand stimulates the offer, thus such actions are of major importance.

It is imperative to ensure that consumers receive trustworthy and relevant information on products at the point of sale, or even from the design phase where appropriate (e.g. in the case they are searching to buy a house) including information on their lifespan performance and the availability of repair services, spare parts and repair manuals.

At the same time, it is equally, if not even more crucial to raise the awareness of professionals of the benefits of redesign and up-cycling of materials and ensuring they are capable of re-using them in their final products. This includes engineers that design constructions, taking into consideration circular economy principles or those that design processes using resources in closed loops (i.e. industrial symbiosis).

But it also includes blue-collar workers, activated in different sectors and many other types of physical work, whose capacity to comply with the new reality must also be built. In this context, if actions are taken in this direction, circularity can be expected to have a positive net effect on job creation provided that workers acquire the skills required by the green transition.

The potential of the social economy, which is a pioneer in job creation linked to the circular economy, will be further leveraged by the mutual benefits of supporting the green transition and strengthening social inclusion.

The importance of local approaches

Circular economy solutions at local level must be tailored to the local conditions and framework. Existing characteristics must be taken into consideration, including around specific waste steams’ from key local economic activities, any dependence on resource imports, current use of materials and any waste exporting activities.

At local level, silos between departments need to be broken to avoid one-sided policy making. Furthermore, circular economy should be a regular theme in citizens’ dialogues. This will help cities to identify and prioritise actions that would create the most important impact, based on an assessment of the local reality and the most relevant materials to be re-entered into the economy

Financing and implementation of necessary local infrastructure supporting this transition is of great importance. For example, material banks and green points for source separation, recycling, re-use and disposing of materials to end-users are necessary.

In this context, the importance of adopting an integrated approach is once again crucial. The new Cohesion Policy funds are expected to help cities to implement such investments, but there needs to be alignment and cooperation of resources and stakeholders at all levels - EU, national, regional, territorial – and including both hard and soft investments.

The prioritisation of actions at local level, to create a hierarchised lists of interventions accelerating the implementation of the Green Deal and the transition to circular economy, represents a future challenge for cities. In this context, additional local criteria could be considered, such as negative effects to the local environment, costs and social acceptability.

Concluding thoughts

The transition to the circular economy needs to be systemic, deep and transformative, in the EU and beyond. To deliver this, a lot of action will be needed at local level.

The nine Cities participating in the URGE project seem to be one step ahead as they have already identified the significance of introducing local strategies, policies and plans for promoting the circular economy. They are also fully committed to digging deeper on these key issues in the coming years.

Although the URGE network is focused on the building sector, it should be possible to generalise its findings and apply them to other sectors. This short article already seeks to serve as a roadmap of actions that cities must critically consider in order to assess, prioritise and implement actions in favour of the circular economy.

These approaches are fully in line with the broader European strategy and aim to place cities firmly as pioneers towards the implementation of sustainability goals at EU level.