For decades, transport decision-makers have predominantly focused on technological advances and diversifying urban transport services to meet growing mobility needs. The common assumption has been that passengers make rational decisions based on travel time and cost. This approach overlooks the complexity of human behaviour. People are not purely rational actors; they are creatures of habit, emotionally driven, influenced by their environment, and guided by social norms and their own self-image.

The Beyond the Urban URBACT network recently held a webinar entitled “Moving People: Using Science to Nudge Behaviours in Transport and Mobility” that introduced this topic to the partners, in advance of a deeper dive into the topic at the planned TNM in Hradec Králové early next year. The attendees learned that to create truly sustainable urban and rural mobility systems, we must look beyond the traditional lens and embrace the insights provided by behavioural science to nudge people towards more sustainable transport choices.

The Gap Between Assumed and Actual Passenger Behaviour

Public transport systems have been designed on the premise that commuters are rational decision-makers who weigh options based purely on journey time and cost. However, behavioural science tells us otherwise. Human behaviour is far more nuanced. We are often driven by habits, emotions, shortcuts, and the influence of our surroundings. Social norms, perceived status, and even the ambient environment can significantly sway our transport choices. For instance, a person might choose to drive not because it is the fastest or cheapest option but because of the perceived status associated with owning a car, or the comfort and autonomy it provides.

What Are Nudges?

Nudges are subtle changes in the way choices are presented that influence behaviour without restricting options or significantly altering economic incentives. They work on the principle of guiding individuals towards a desired choice by leveraging psychological insights. While the private sector—such as the car industry—has effectively utilised behavioural nudges for years to promote certain behaviours (like buying a specific brand or model), public policy has been slower to adopt these methods. If public transport systems do not harness these insights, they may be at a disadvantage in encouraging more sustainable behaviours.

Key Principles of Behavioural Science in Transport

To understand how to nudge people towards sustainable mobility, it is crucial to understand key behavioural science principles that affect decision-making processes. Traditional theories like Rational Choice Theory assume individuals make decisions based on a rational evaluation of all available information. However, in practice, choices are often irrational and influenced by biases. This is where the concept of Bounded Rationality comes into play, recognising that people make decisions based on limited information and cognitive limitations, leading to suboptimal choices. Moreover, the Dual-Process Theory suggests there are two systems of thinking—System 1 (fast, automatic, and emotional) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, and rational). Most transport decisions are made using System 1, influenced by emotions and habits rather than rational deliberation each and every time.

Many passengers think they are motivated by a range of factors, but most decisions are actually driven by five key elements: status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness. Status plays a role when people choose transport options that confer social prestige, such as driving a fancy car or taking a faster, more prestigious mode of transport. Certainty is about the reliability and predictability of transport, where passengers prefer modes they can trust. Autonomy is a significant factor, where people desire control over their journeys, such as the flexibility that comes with driving a private car. Relatedness involves a sense of connection or safety, such as travelling in environments that feel safe and friendly. Fairness revolves around the expectation that the pricing of transport modes should reflect the value they provide.

The Influence of Environment and Context in Transport Choices

Beyond these motivational factors, environmental and contextual influences play a crucial role in shaping transport decisions. The Default Effect, for example, highlights that people are more likely to stick with pre-set options, which can be used to promote sustainable transport modes. Framing Effect is another significant concept; it illustrates that the way information is presented can greatly affect decision-making. For example, the perception of time in transport contexts can be manipulated: walking may feel longer than cycling for the same duration, but it feels shorter than waiting at a stop. A calm ambiance, with warm lighting and relaxing music, can also shrink perceived travel time. Interestingly, studies show that passengers perceive return trips to be about 22% faster, and the anticipation of arriving at a destination often creates a ‘watched pot’ effect.

Spectrum of Nudges and Real-World Examples

Behavioural nudges can be categorised across a spectrum that ranges from passive to active, generalised to personalised, and from time-based to event-based. This spectrum reflects the varying degrees of subtlety and specificity with which nudges can be applied to influence commuter behaviour towards more sustainable choices. By understanding and employing different types of nudges, cities can strategically design interventions that address specific challenges in urban mobility.

1. Passive Nudges: Passive nudges are subtle interventions that gently steer individuals towards a desired behaviour without requiring conscious decision-making. These nudges are often embedded in the environment or default settings. For example, Default Effects are a powerful type of passive nudge; when the most sustainable option, such as opting into a public transport subscription, is set as the default, most people will stick with it. An example of this is in Copenhagen, where default bike lanes are integrated with public transit systems to encourage cycling and use of public transport over driving.

2. Active Nudges: Active nudges require more engagement and conscious decision-making from individuals. They are designed to capture attention and encourage specific actions. One well-known example is the Piano Stairs in Stockholm, where a staircase was transformed into a giant piano keyboard that played notes as people walked up and down. This nudge encouraged people to take the stairs instead of the escalator, promoting physical activity. Similarly, 3D zebra crossings that create an optical illusion of being raised from the road have been implemented in places like Iceland and India to slow down traffic and enhance pedestrian safety.

3. Generalised Nudges: Generalised nudges are broad-based interventions aimed at influencing the behaviour of large groups without tailoring to individual characteristics. For instance, in Copenhagen, the concept of Green Waves for bicycles is a generalised nudge. Traffic lights are synchronised so that cyclists maintaining a consistent speed of around 20 km/h can hit a series of green lights without stopping. This not only encourages more cycling but also promotes a steady pace, reducing the likelihood of accidents and making cycling a more attractive mode of transport (Picture: "'Green wave' sign for cyclists, Copenhagen" by philip.mallis).

3. Generalised Nudges: Generalised nudges are broad-based interventions aimed at influencing the behaviour of large groups without tailoring to individual characteristics. For instance, in Copenhagen, the concept of Green Waves for bicycles is a generalised nudge. Traffic lights are synchronised so that cyclists maintaining a consistent speed of around 20 km/h can hit a series of green lights without stopping. This not only encourages more cycling but also promotes a steady pace, reducing the likelihood of accidents and making cycling a more attractive mode of transport (Picture: "'Green wave' sign for cyclists, Copenhagen" by philip.mallis).

4. Personalised Nudges: Personalised nudges target specific groups or individuals by tailoring messages or interventions to their preferences or behaviours. For example, personalised travel planning apps that provide real-time data on the best routes, considering both environmental impact and user preferences, can nudge users towards more sustainable travel choices. In London, Transport for London (TfL) has experimented with sending personalised travel advice to commuters based on their past travel patterns, nudging them to consider alternative routes or modes of transport during peak times to alleviate congestion.

5. Time-Based Nudges: Time-based nudges are interventions that occur at specific moments when people are more open to change, such as the start of a new year or during a move to a new city. For instance, launching a public campaign to promote cycling or public transport at the beginning of spring, when the weather is favourable, can be more effective. Several cities across Europe have now successfully implemented a congestion charge to nudge drivers out of their cars at specific times, particularly during peak hours, significantly reducing traffic in their respective city centres.

6. Event-Based Nudges: Event-based nudges are designed around specific occurrences, such as local festivals, construction projects, or environmental crises. During such events, temporary nudges can encourage sustainable behaviour. For example, some Japanese metros use unique arrival jingles for each station, which serves as a behavioural cue to help passengers know when their station is next without needing to check. This reduces anxiety and improves the overall passenger experience, subtly promoting the use of public transport.

7. Sensory Nudges: Nudges that engage the senses, such as sound, sight, or even smell, can influence transport behaviours by altering perceptions of comfort, speed, or time. For example, one study in the UK found that sounds of nature had a more relaxing effect on a group of commuters than listening to music or podcasts.. Similarly, stations with cleaner environments and aesthetic enhancements are perceived as safer and more welcoming, which nudges passengers to opt for public transport.

8. Gamification and Incentive-Based Nudges: Gamification leverages elements of game design to encourage sustainable transport behaviour. For instance, experiments in the Netherlands and Czech Republic enabled commuters to earn money and rewards for choosing sustainable travel modes. These points can then be exchanged for discounts or benefits in local shops and services, creating a positive reinforcement loop that encourages ongoing sustainable behaviour.

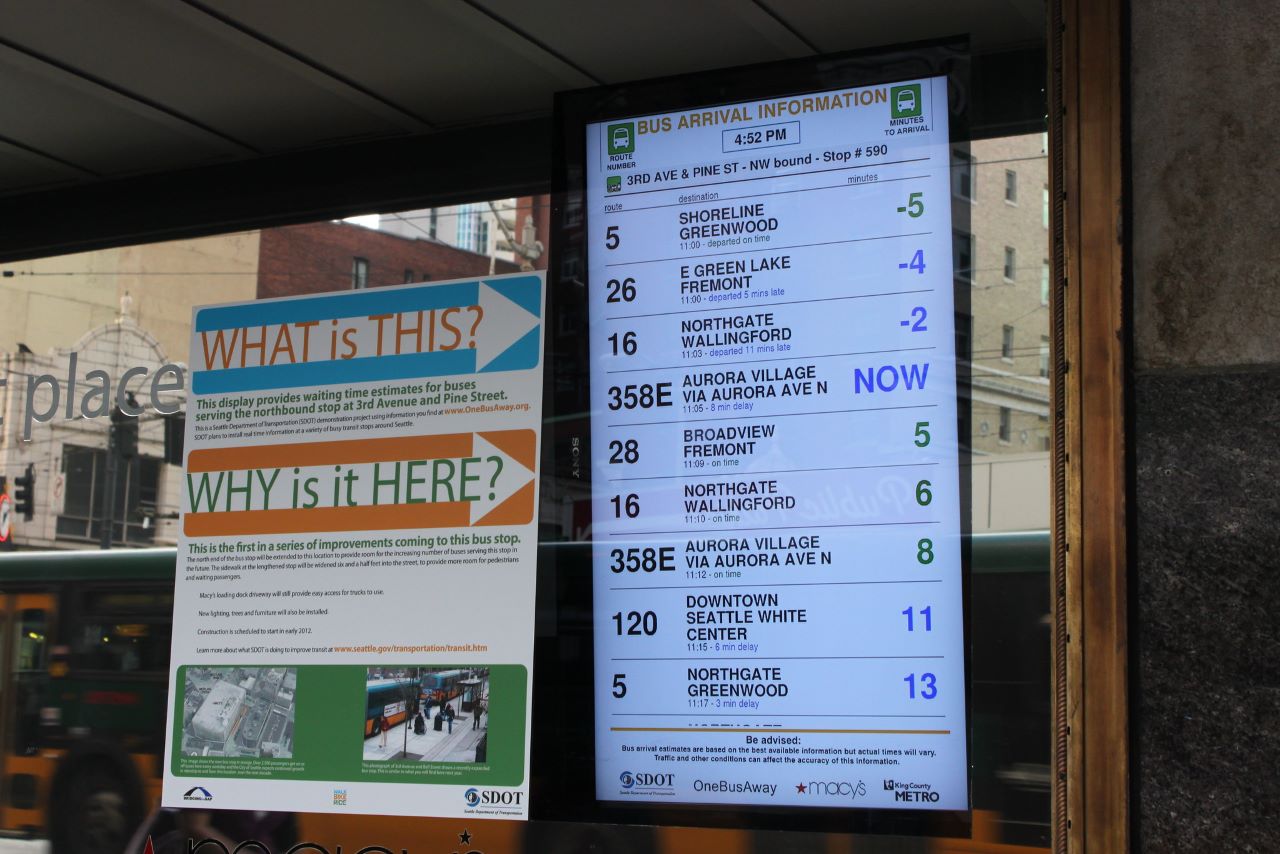

9. Visual Cues and Informational Nudges: Visual cues can provide immediate feedback to travellers. An example is the use of digital displays at bus stops and train stations, which show real-time information about delays or alternative routes. Providing such information can reduce frustration and make public transport seem more reliable.

"Real-time bus arrival information display" by Oran Viriyincy is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Copenhagen’s "nudging litter into bins" initiative uses visual cues like footsteps painted on the pavement, leading to bins to encourage proper disposal of waste, thereby keeping public transport stations clean and pleasant.

Combining Nudges for Greater Impact

Effective nudge strategies often combine multiple types of nudges to maximise their impact. For example, a city could implement a Green Wave system for cyclists (generalised nudge) while also sending out personalised notifications to commuters (personalised nudge) to encourage them to switch from driving to cycling. In another example, 3D zebra crossings can be combined with a public campaign and temporary incentives, such as a reward for students to walk to school, to create an engaging multi-layered intervention.

Designing Effective Nudges: The "Due EAST" Framework

To create effective nudges, policymakers can follow a structured approach involving defining, designing, testing, evaluating, and iterating on nudge strategies. The EAST framework is particularly helpful for designing these strategies. It suggests making nudges Easy by simplifying messages, providing clear next steps, and reducing barriers. They should be Attractive, ensuring relevance to the audience and sometimes adjusting the tone to suit different groups—formal for some, casual for others. Nudges need to be Social, leveraging social norms and the behaviours of peers. Lastly, they should be Timely, acting at moments of change or decision points to maximise impact.

Conclusion: Time for Action

The Beyond the Urban network brings together ten European municipalities and regions that will collaborate with the aim of improving urban-rural mobility through the testing and implementation of sustainable, accessible and integrated mobility solutions, and behavioural science offers a powerful toolkit for nudging people towards more sustainable transport choices. By understanding the psychological and environmental factors that influence decision-making, territories can develop targeted strategies that not only encourage, but make it easier for citizens to choose sustainable options. The key is to test, learn, and iterate. As we embark on our small-scale actions and pilot projects in the network, now is the time for cities to embrace these insights and take concrete steps toward a more sustainable future.

You can retrieve the entire webinar on Youtube below: