In the 1990s, people usually limited their daily commute to going from home to the workplace, every day at the same time (and vice versa). Other minor trips, often related to care tasks, were either integrated into these journeys or embarked on by one of the family members who took care of the household.

Because of these dynamics, experts have historically developed descriptive mobility models based on surveys, where people expressed their major daily journeys by indicating origin and destination. These models assume that these trips are repeated every working day, week after week, and year after year. In this context, infrastructure faces the challenge of coping with peak travel hours, combined with a ridership drop-off for the rest of the day.

The depletion of fossil fuels, the impact on the environment, and the need to distribute mobility peaks to other time slots or care-related activities have been some arguments that have facilitated the transformation of mobility rhythms and modes.

Nowadays, everyday mobility has become more complex. As a result, describing these movements is a hard task. For example, teleworking a few days a week (or almost daily) has become normal. It is common to require even greater mobility for work, with weekly commuting distances of 500 km. Indeed, long-distance commuting is becoming an integral part of work routines.

Our society is more multifaceted and, as a result, so is mobility. In a day, besides work, we go to the gym, go shopping, meet friends and pick up our children from school. For example, in the case of Spain (where telecom mobility data is available), we can state that the number of trips in 2023 compared to 2019 is only 2% less. However, the total distances travelled were reduced by 12%. A detailed analysis confirms that trips under 10 km have increased, while long-distance trips have decreased.

Therefore, mobility has changed its rhythm. It is sensitive to variances from one day to the next; it presents a challenging pattern because it is erratic. This change of scenario confronts us with new challenges: the first is how to measure this mobility to improve its design and management in terms of sustainable urban development.

This implies understanding whether the systems used up to now, aimed at measuring systematic mobility, are valid when mobility becomes erratic. It also involves exploring new methodologies that go beyond measuring the average daily traffic of vehicles to estimate the hierarchy and capacity of roads (carried out with great effort by administrations through manual counts), developing "Daily mobility surveys" (EMQ) periodically or analysing public transport inflows (through tickets or other loyalty systems).

Today, it is possible to measure other aspects of mobility, like journeys between different points of the territory through credit card transactions or mobile phone data. These data allow us to build origin-destination matrices with information aggregated by different time segments and demographic profiles (gender, age, local/tourist, etc.). We can also create a real-time picture of the frequency of public transport thanks to the Transit Feed specifications standardisation, which goes beyond the network coverage of traditional isochrones (travel time catchment area).

On the other hand, thanks to mobile applications and sensors deployed in the city, we can gather information about parking and its occupation or the loading and unloading of goods - which today is another of the major mobility disruptions.

If people's mobility gradually decreases, a cloud of micro-mobility emerges around them: riders moving food and goods or the last-mile logistics frantically connecting homes with the various warehouses around the territory. Micro-mobility is growing at high speed and is filling the streets that we had emptied.

This entire ecosystem of data helps us to interpret the logic of urban mobility in whole new ways, which leads to more informed decision-making in cities. It also enables us to anticipate negative impacts such as poor air quality or noise, or even, in a scenario of mobility reduction (driven by the ecological transition for example) foreseeing possible risks of social segregation.

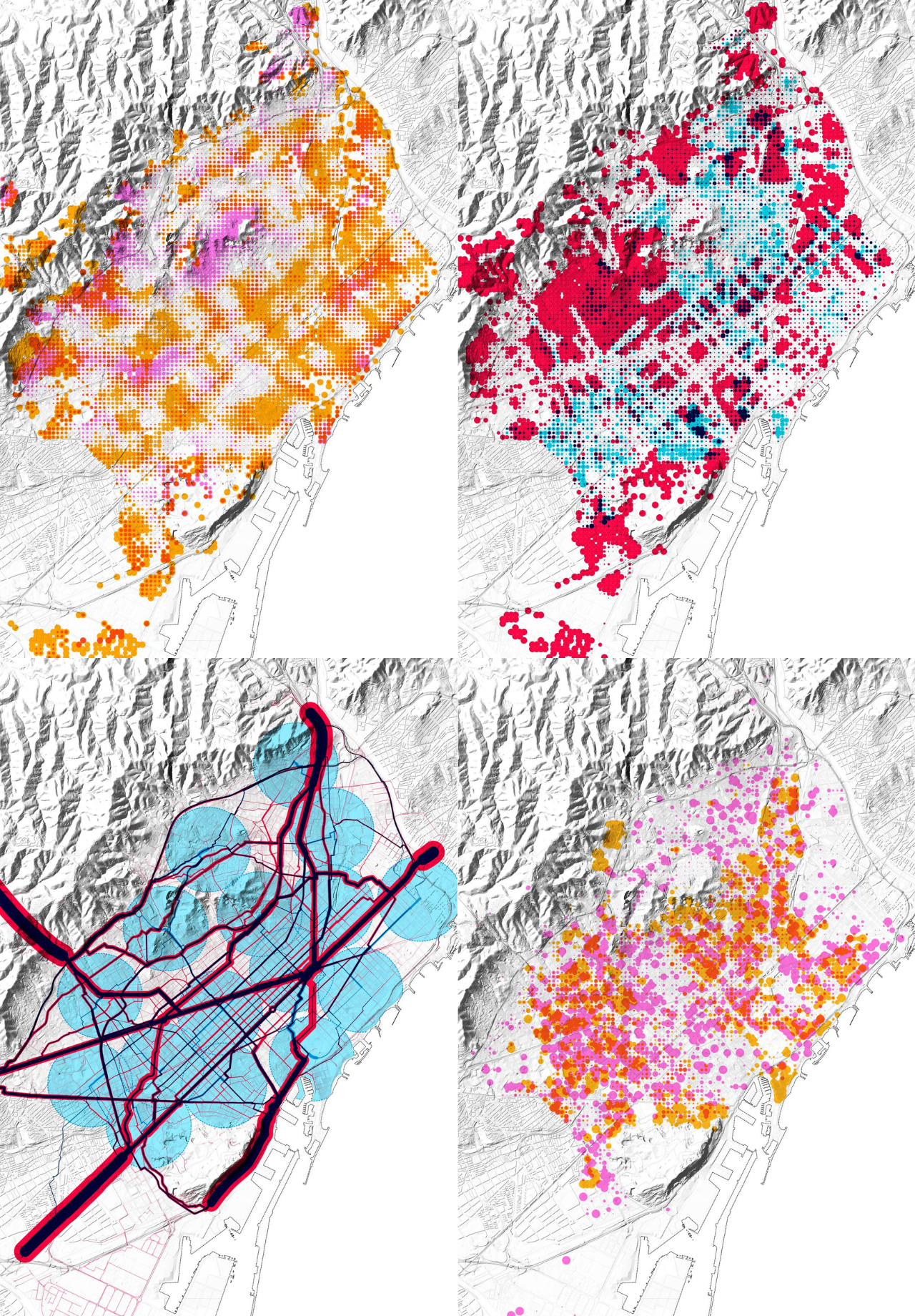

This series of images displays several layers representing the accessibility to sustainable mobility modes (public transport and bicycle), the impact of last-mile logistics and the availability of parking spaces in Barcelona arising from the research Air/Aire/Aria (https://air.300000.eu/).

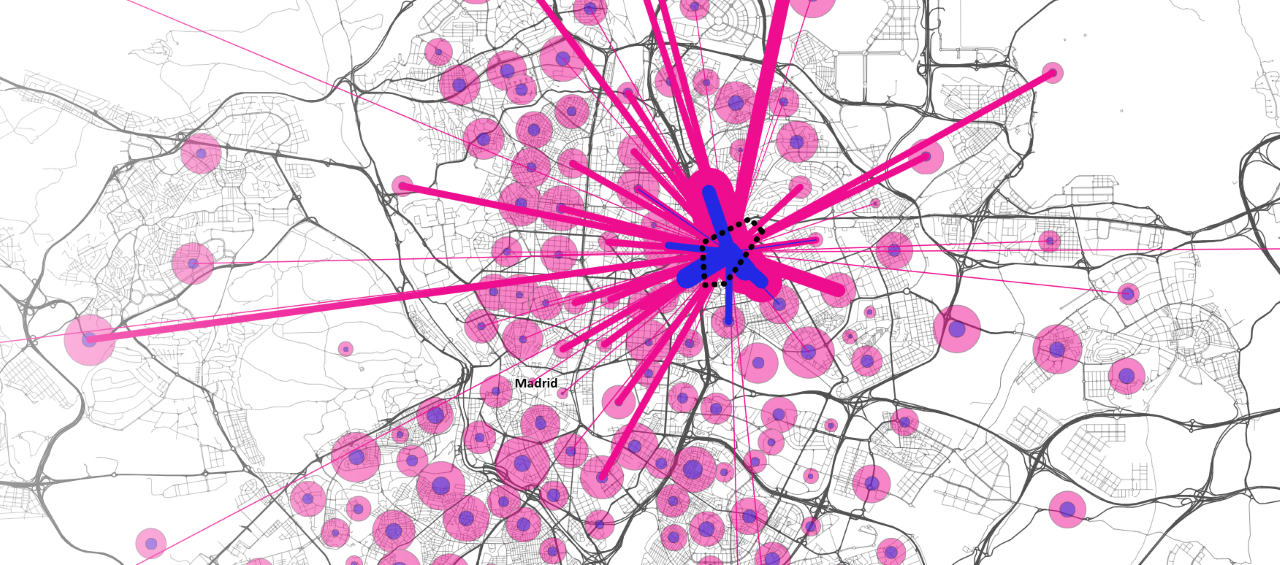

The image displays the mobility matrix (mobile phone data) before and after Covid-19 from the project Embarriados (https://embarriados.cotec.es/), which explores the potential social segregation arising from the mobility reduction.

The first webinar of the Urbact Beyond The Urban network presented all these aspects, from the possibility of accessing information to the need for institutions to have the capacity to analyse and subsequently make informed decisions. The different municipalities and regions in the network commit to improving urban-rural mobility through testing and implementing sustainable, accessible, and integrated mobility solutions. They focus on inter-modality, multi-level governance, inclusion, gender equality, and digital tools.

The webinar has triggered an internal reflection within the partnership according to the different maturity levels of each region regarding the use of data for mobility policies. For example, some participants initially believed they did not need data (because they worked in a very delimited environment) and suddenly saw its potential.

On the other hand, other participating regions stated that they did not have data when, in fact, they do have data and have started to understand how to use it and how to cross-reference it. Other partners, with a good starting level of information, have expressed the need for more data while also understanding the need to test the insights they can gain from the data they already have.

As a result, the partnership has started building a mutual understanding of the potential of data technologies, with some regions expressing their willingness to focus on data collection in the coming months and work with their ULGs on some of the presented questions.

In conclusion, although the Beyond The Urban municipalities present very different characteristics and needs, they all share the common challenge of building a pathway that involves understanding what data is available, how to create it, and what questions it answers.

We will still likely need mobility surveys to track changes in our cities with the situation thirty years ago. However, we will need new ways of measuring mobility, capable of dealing with its randomness and scale. We will need to build on existing knowledge and dare to experiment with novel data sources and methodologies while identifying the relevant information to understand ourselves and ensuring its availability - to reclaim it and guarantee its sovereignty.

You can retrieve the presentation in PDF at this link and the entire webinar on Youtube below: