Lisbon has developed a participative model for working in deprived neighbourhoods using the instrument of Community Led Local Development (CLLD) funded by the European Regional Development Fund. There are very few models of urban CLLD across Europe. Lisbon and the Hague are the two best examples. This paper looks in detail at the BIP/ZIP in Lisbon, which has been awarded an URBACT Good Practice Label in 2017.

The Lisbon BIP/ZIP strategy aims to promote social and territorial cohesion, active citizenship, self-organisation and community participation. Lisbon’s approach addresses the fracture of communities due to social, economic and environmental issues. When Lisbon started BIP/ZIP in 2010 their main idea was to identify neighbourhoods that were lacking social cohesion and suffered poor socio/economic, urban and environmental conditions. Most of all these areas lacked a meaningful connection between local citizens and the local authorities and so BIP/ZIP sought to build a new relationship through working together on relatively small projects of less than 50,000 EUR to improve conditions. The programme has been running across two EU programme periods starting in 2010 before the new CLLD article in the regulation. It is funded out of the National Operational programme (ERDF).

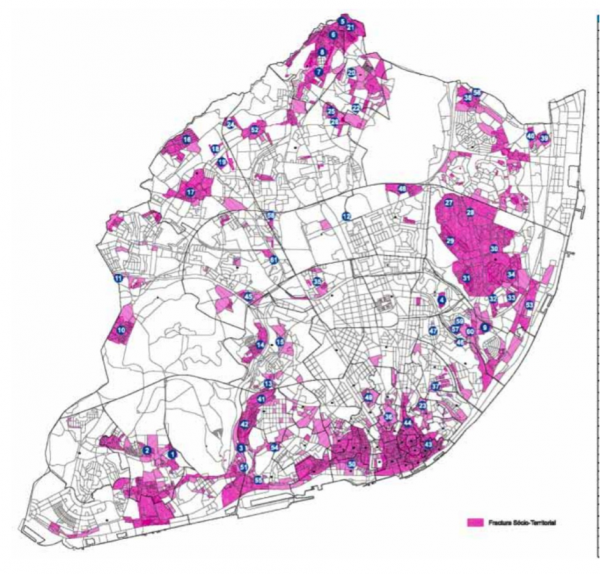

The Design of BIP/ZIP: A first mapping of the city’s social and territorial fractures.

Lisbon collected statistical information about social, economic, urban and environmental factors to see which areas are the most deprived in the city and Lisbon surveyed these areas; Lisbon identified and mapped the city’s social and territorial fractures. This kind of mapping was a first in the city and in the country: a truly innovative concept in 2009-2010, using a scientific data driven approach to identify the real problems facing citizens. Lisbon used national decennial census data and other municipal and government data that is more up-to-date. Lisbon crossed many datasets and maps in order to understand social and territorial dynamics.

Lisbon identified 67 neighbourhoods across the city, mixed between those areas in the peripheral housing estates and those in the historical centre. Altogether the areas cover 141 126 out of a total Lisbon population of 547 733 (approximately a quarter of Lisbon’s population).

A participatory governance model

At the city level there is a Community-Led Local Development network which acts as the Local Action Group. This is an interesting interpretation of the ERDF regulation and is structured to meet the regulation, with no sector having more than 49% of voting membership.

Before BIP/ZIP was launched there was an extended public consultation with a wide range of stakeholders. The idea was to improve the relationship between citizens, NGOs and Council services. Participation both in looking at neighbourhood problems and in promoting innovative solutions is at the heart of the approach.

Although the starting point of definition of the areas is the data, the boundaries are hard to fix because they have to make sense in terms of identity and other factors in the neighbourhoods.

Each year an open call is made to organisations in the 67 areas. The call is normally published in the Spring and is kept open for 3 months. A key eligibility criterion is that an organisation must have at least two sponsor organisations working together. It follows that no applications from single organisations are accepted. The bid can be up to 50 000 EUR and the project must be completed within 12 months and should be sustainable in the long term which is defined as lasting two years after funding ceases. Organisations are required to analyse the situation, build their partnership, establish objectives and results to be achieved and then define activities to achieve these results. The applications are first sieved by the local elected borough council. They do an initial prioritisation before applying to the City-wide programme for approval of their short-listed projects to the municipality.

The programme is open to non-profit organisations and informal groups such as a resident’s association. Informal associations have to partner with formal organisations but since each bid has to have a minimum of two partners this is normally not a problem. Lisbon has an online application process and any initiative can apply and will be considered for selection if they satisfy the eligibility rules.

More than 230 projects already funded

By 2017, Lisbon had received approximately 500 applications and funded more than 230 projects, all of them small initiatives across the city. The budget had been around 9 million euros so far. A total of 400 organisations have been involved in delivering in BIP/ZIP projects in the past five years.

Applications for BIP/ZIP are openly listed on the website according to the edition year. In 2018, 39 projects were selected out of 106 bids. The mix of projects is diverse. Typical projects that have been funded include:

- Improvements to pocket parks and play facilities

- Project to combat gender-based violence

- Small scale environmental improvements

Local offices called GABIPS have been created to support the CLLD process in a selection of area. These bring together municipal officers, elected members and local actors. There are seven of these offices covering 16 of the local areas and ten districts: Padre Cruz, Augis, Mouraria, Boavista (see article on housing in Boavista by Laura Colini), Alto da Eira, Ex-SAAL, and Almirante Reis They help to guide the initiatives and investments in the local areas. They each have a coordinator from the The GABIPs allow the municipality to move decision making to the local scale and share it with local actors.

Lisbon are working on the revision of the BIP/ZIP map based on survey data and will compare it with the previous map to understand how the city has been changing since the start in 2010.

Snapshot on Mouraria

Mouraria illustrates that the CLLD approach with a few projects needs to be complemented by other physical and enterprise initiatives.

Mouraria is a working class, multi-ethnic district close to the centre. By the early 2000s it had become very run-down and has been the target of a range of integrated urban regeneration efforts involving the local community since before the start of the CLLD in Lisbon. There had been major investment in public realm, particularly the squares and streets in the centre of the area as well as Community facilities. One project has profiled well known local characters by featuring their images on the walls.

Mouraria has also been the focus of other policies by the municipality which aims to reinvent Lisbon as an entrepreneurial and innovative city. The city has witnessed an explosion of coworking spaces and incubators in the last decade, supported by the city authorities and increasingly located in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Mouraria Creative hub is located in a former palace and has space for 50 creative entrepreneurs.

It is stimulating the creative economy of the city and providing a focal point for local entrepreneurship activity while contributing to regeneration of the neighbourhood economy.

Mouraria illustrates that CLLD can be linked to other city strategies both for regeneration and for enterprise and transport. In Lisbon the BIP/ZIP complements other policy interventions and boosts community engagement more widely. It does not replace or substitute for these other mainstream policies.

Partly because of its location and ambience and partly because city policies have made Mouraria more desirable it now risks becoming a victim of its own success. Some large scale apartment developments are being built. The area is frequently cited in reviews of Lisbon in trendy papers.

A walkshop around the neighbourhood is planned during URBACT City Festival 2018.

Lessons for other Cities

BIP/ZIP has become an important policy of the municipality and generated many partnerships at the neighbourhood scale.

Overall, the BIP/ZIP approach to CLLD deployed by Lisbon offers a way forward for urban authorities that want to use the CLLD regulation either as a freestanding tool or as part of an integrated

development for a city funded under Article 7 of the ERDF, for example within an Integrated Territorial Investment. BIP/ZIP counters the prevailing paradigm of infrastructure led investment and allows local communities to get important but small-scale projects financed. However, it does not have the resources to combat the wider problems of deprived neighbourhoods, or to address market led initiatives which promote gentrification at the expense of local citizens. These can only be fixed by concerted multi-level action across a wide range of policy areas – many of which are not under the control of cities.

Despite its budget limitations BIP/ZIP shows what is possible to achieve through community led local development. In particular, they have made a sustained effort to engage with local actors to make change happen. Cities all over Europe need to get out of doing things to neighbourhoods in a paradigm supported by the development industry and follow Lisbon in embracing an approach to working with communities and building on their assets.