"It is employers who create jobs" If cities are to help young people to get the jobs they need, then engaging with employers is pivotal to success. Success requires the creation of more and better jobs for young people to do. It means employers, large and small, public and private, from local start-ups and microbusinesses to national and international corporations with branches in the city, recruiting more young people, retaining them, developing them and providing opportunities for them. So, employer engagement needs to be at the heart of city action to meet the youth employment challenge.

This is an excerpt of the article featured in the URBACT Capitalisation 'Job generation for a jobless generation,' to read the full article click here.

In URBACT’s work with cities we came across a range of experiences of cities working with employers, from working with schools to assisting employers to take on young people. In our ‘state of the art’ review, we found that employer engagement was widely examined and seen as vital, by organisations like the OECD. And at our hearing in Brussels in the autumn of 2014, where we drew together representatives of young people, employers, cities, experts and practitioners from countries across the EU to meet with our core group, we found great interest in improving employer engagement. This article distils the key messages from this work for cities: what they can do and how might they do it.

So, what are the concrete city actions that deliver results?

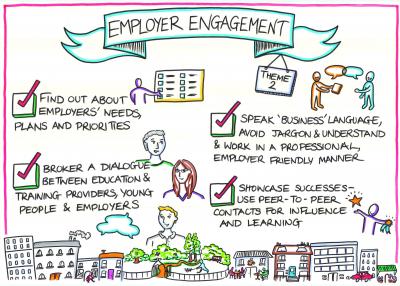

Find out what employers need

At a minimum, cities need to have a clear idea of what employers’ needs are: what jobs (vacancies) do they have available, and are likely to have available, in the future? What skills do they need? What jobs are they finding hard to fill because of skill deficiencies? How do they go about recruiting young people? What more could they do to recruit young people? Why do employers not hire young people? For example, in Leeds City Region the Local Enterprise Partnership uses a biennial employer survey assessing their skill needs, the extent and nature of skills shortages and gaps, underemployment and how these vary by sector and occupation. A sample survey can not only identify particular needs but also broader patterns that can then be addressed.

Give information, advice and guidance

Young people, if they are to make well informed choices as they move from education into the labour market, require sound information on jobs, the skills they need for them, earnings and so on. Close relations with employers enables access to this information and they are often willing to help develop career materials, give talks, attend events and even provide mentoring. Cities are in a good position to gather together information on employer needs and labour market trends and then produce attractive materials for young people to help guide their education, training and job decisions. In Leeds City Region the Local Enterprise Partnership has produced a series of sector factsheets detailing job trends and opportunities, wages, qualifications required and so on, for use in careers counseling

Build long term relations between employers and the education system

The transition from school to work is crucial for young people. Whilst there is value in individual employers and individual schools, colleges and universities developing relationships with each other for mutual benefit, to ease this process for young people (and employers) cities can play a strategic role in systematising these, encouraging them, demonstrating the benefits of them and putting in place measures to assist greater responsiveness of education providers to meet employer needs. They can establish incentives (financial, behavioural or moral) to do so and measure (in part) local providers (and employers) on their degree of success in securing young people access to jobs and further appropriate training. In Wrocław, Poland, partner in the URBACT Markets network, the growth of foreign inward investment and the need to move up the value chain, has changed the local labour market, driving demand for more highly skilled young people. They have developed relations with schools, increasing the vocational component; and created an academic hub to encourage university/economy collaboration. Building these bridges between the worlds of education and work, helps prepare young people for the world of work, increases the likely relevance of vocational education and training and raises awareness on all sides – employer, education provider and young person.

A permanent dialogue

Cities can go further, and establish a more intense and long-term arrangement, by setting up an independent body or partnership, perhaps including other key stakeholders (such as the public employment service, education and training providers and young people themselves) to oversee the operation of actions to meet the youth employment challenge. Cities can also develop relations with key individual employers who exhibit good practice from which others can learn and which can inspire young people. For example, Sky Broadcasting are keen to secure their future talent pipeline and have established the Sky Academy, to help young people reach their potential and give them the skills they need to do so. They run programmes with star athletes as mentors in schools; provide opportunities to use state of the art technology to create news reports; and provide work experience, work placements, apprenticeships and graduate programmes.

Co-creation

From sustained dialogue, it is a short but important step to the co-creation by partners of an integrated strategy to address youth employment. Establishing together a vision, priorities, objectives and an associated action plan, which is regularly monitored and reviewed is not only likely to lead to a more co-ordinated approach and draw on all the talents available, but also to achieve more effective outcomes. It can help lock in commitment and secure a common purpose. And it may be more able to tackle the ‘wicked issues’ that arise e.g. the balance between differing levels of skills provision; the links between education, employment and economic development policies. As the emphasis of action moves from the supply side (young people) to the demand side (jobs), wider issues than young people arise like inward investment, sector and cluster policy, supply chains, business development and competitiveness.

But we need to challenge employers too!

It is not always the case that meeting existing employer needs and creating more opportunities for youth go hand in hand. Encouraging and persuading employers to increase opportunities may not be enough. There will remain employers who are shedding youth labour, offering few new openings, provide low pay, no work experience or apprenticeships and are reticent or unwilling to engage with the city and other stakeholders. Change is best addressed through peer to peer (i.e. employer to employer) interaction with employers learning from each other, from good practice and role models, from successful companies sharing their experiences with others, perhaps in sector groupings or in supply chains. The role of the city here could be to provide the background research necessary (to support the business case for such action) and support such developments as required. In Leeds City Region, for example, it has been calculated that moving 1,000 people into work generates a combined fiscal and economic gain of €25 m per year.

And what about young people?

Engaging young people, and in particular providing opportunities for young people to speak of their own experiences and ambitions, is also valuable. Listening to their voices and facilitating and encouraging dialogue with employers, will help to enhance mutual understanding and raise awareness both of what young people have to offer and what employers are looking for. It may also spark innovation in how they connect with each other on the labour market.

It bears repetition: it is employers who create jobs. We need more, and better, jobs for young people to do. Employers are at the heart of the solution. So are cities. Cities need to get engaged to employers, if not married.

By: Professor Mike Campbell

Read More:

Job Generation for a Jobless generation - URBACT Capitalisation

Case Study - Leeds City Regions: Towards a NEET-free city – URBACT Capitalisation

Case Study – Supporting young creatives in Thessaloniki: a bottom-up approach – URBACT Capitalisation

Photo Credit:

Image 1: Handpeak Project: Paraskevi Kokolaki – Yiantes, Design and manufacture of handmade jewellery and accessories. Source: Spyros Tsafaras

Image 2: Alison Partridge

Image 3: Employer engagement. URBACT workstream ‘Job generation’, 2014 by Rachel Walsh

Image 4: Freepik