Photo by François Jégou

Urban garden in Mouans-Sartoux (FR).

How can we bring the transition issues related to food back to the table and to citizens' attention? Get the highlights of two URBACT Networks, BioCanteens and BioCanteens#2, led by Mouans-Sartoux, an URBACT city that is holding the next EU City Lab on Changing Habits for a Healthy and Sustainable Food System.

"These collective gardens grow vegetables and fruit, but above all they produce socialisation between the inhabitants of the neighbourhood", says Rob Hopkins during a visit to one of the Citizen Feeds the City‘s six gardens, a project that was conceptualised by the MEAD - Sustainable Food Education Centre and set up by the local residents of Mouans-Sartoux (FR).

What the famous creator of the Transition Towns movement nicely calls as "patchwork farming" offers the potential to feed a few families in the neighbourhood, but as the URBACT Network Sustainable Food in Urban Communities has clearly shown, it actually represents an important symbolic vector for local gatherings and the transformation of the inhabitants' food practices.

À TABLE ! IN TRANSITION

As an echo, at the opening of the "Mouans-Sartoux Food Forum - A Table!" the city’s Deputy Mayor in charge of Children, Education and Food, Gilles Pérole, shared with participants the first results of a carbon impact evaluation that was carried out at local level. Over the period between 2016 and 2022, this study was conducted under Andrea Lulovicovà's thesis at the University of Cote d'Azur and with financed from ADEME. According to the evaluation, while food represents a yearly average of 2 tons of carbon per person in France, it is only about 1.17 tons in the city of Mouans-Sartoux. The average diet of the locals has an impact of 43% of carbon emissions, when compared to the national average. In addition, the number of inhabitants eating less meat has increased to 85% in less than 10 years.

Considering that the food sector roughly represents 1/3 of the greenhouse gas emissions in our European lifestyles, Mouans-Sartoux's food policy achievements become even more impressive. These results are also proof that when it comes to changes “the carrot and the stick approach" is not always the best solution – take for instance the Netherlands, where meat advertisements are banned. The "Mouans-Sartoux approach" is a bearing fruit, as it builds instead in the long-term awareness and education for a sustainable transition.

Photo by François Jégou

Group discussion during the A Table ! Mouans-Sartoux Food Forum.

The city's "permanent public activism" is proving its effectiveness with the Citizen feeds the city urban gardens, but above all, it has proven its worth with the 100% organic and almost exclusively local canteen where 1 000 primary school children eat every day – being half of the meals strictly vegetarian. Also, the influence of "zero food waste" on families, the municipal farm located 700 meters away from the town centre that supplies the school kitchens, the three municipal agents-farmers who harvest 25 tons of vegetables per year and the municipality's support for the installation of young organic producers on communal land are among other successful measures.

At last, the municipality has also succeeded to create the MEAD - Sustainable Food Education Centre: the city true public food service. The centre is politically committed to fair trade and it supports the Positive Food Families Challenge As Valery Bousiges, a parent from a primary school student, who we met at the start of the first URBACT BioCanteens Network in 2018, summed it up: "The question is not when is something happening about food in Mouans-Sartoux, but what is happening today. We are being asked every day!".

The “A Table !" Mouans-Sartoux Food Forum” brought together more than 150 stakeholders from 10 countries – including 50 local authorities, more than 20 NGOs and official structures involved in the food transition – on the occasion of the closing of the URBACT BioCanteens #2 Network from September 26 to 28, 2022. The title of the event was spot on: how can we bring the transition issues related to food back to the table and to the citizen’s attention?

According to François Collard-Dutilleul, from the Lascaux Centre on Transitions, food sovereignty – which was the central theme of the Forum – means reclaiming the ability to choose what we put on our plates. This goes far beyond the oversimplified idea of food autonomy, which is so often put forward after the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

As Andrea Lulovicovà, who now works with the Greniers d'Abondance, and Chantal Clément, from IPES FOOD, remind us, the food transition rests on three critical pillars: the agricultural transition, the relocation of food and the transformation of food practices. It is not enough to produce organic and local food if we do not change the way we eat. The example of Mouans-Sartoux and all the other towns in food transition tick all three boxes.

Bio Sceptics card game

Card game called ORGANIC SKEPTIC: We all have a good reason to distrust organic certification The cards are spread over the table, with a myth busting messages

Bio Sceptics

In his book “L'Homnivore”, Claude Fischler, explains that through the mechanism of “food embodiment”, we become what we eat. This applies both physically and symbolically, hence an increased resistance to any diet changes. Unless our lives depend on it, like they once did for the first humans, dietary changes can threaten one’s identity altogether.

We have seen such a resistance about organic food in all partner cities from the BioCanteens #1 and #2 Networks: "organic food is not reliable, not useful, not healthy, not sustainable, not...". To acknowledge that it’s scientifically proven that organic is better for your health and for the planet, it means to become aware of the fact that the conventionally grown food that most of us eat every day is poisoning – not just for us, but also for the world.

To explore the hidden psychology behind organic food, the BioCanteens team has developed the "Bio Sceptic" card game, which gathers the scepticism clichés heard from farmers, traders, consumers, municipal services and others. The game provides the knowledge and arguments of field actors, toxicology and certification experts to reduce any misconception towards organic certification.

Organic certification is essential for the food transition, human health and societal resilience. It is not without its problems and it can certainly be improved. Playing with stakeholders in the territory, the game consists of finding all the argument-cards responding to each mistrust-card. Thus, discussing them, opening the debate, targeting the main controversies, defusing some misunderstandings or irrational fears and, most importantly, highlighting some concrete problems that still need to be solved.

Photo: François Jégou

Participants of the A table ! Food Forum in Mouans-Sartoux (FR) playing the Bio Sceptics card game.

CITIES IN FOOD TRANSITION

But what are all these cities in food transition doing and how can we support their movement at national and European level? During the second part of the Mouans-Sartoux Food Forum, participants were asked these questions in the marketplace booths, where an open-air market was set up to promote exchange and provide some food for thought.

In these booths participants were invited to discover the journey from cities in transition, particularly the BioCanteens #1 and #2 partner cities: Gavà (ES), LAG Pays des Condruses (BE), Liège (BE), Rosignano Marittimo (IT), Torres Vedras (PT), Trikala (EL), Troyan (BG), Vaslui (RO) and Wroclaw (PL). These partners have adapted and transferred Mouans-Sartoux’s Good Practices in different ways.

During this process the cities have also gathered their own local Micro-Good Practices when cooking and in terms of food education in the canteens. In the booths, interested visitors could also check the BioCanteens toolbox, which is composed of a projective exercise on the Food Sovereignty of each city and the future of its food-producing land by 2040, in addition to a simulation game to create a Municipal Food Platform, a poster outlining a Multi-Level Food Governance Plan and the Bio Sceptics card game.

Photos: François Jégou

Market place at the A Table! Food Forum in Mouans-Sartoux (FR).

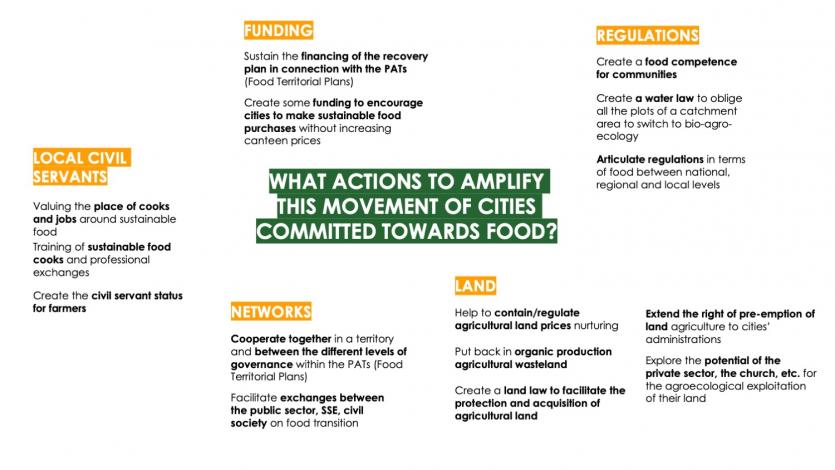

In one particular booth, participants were asked to consider what actions should be taken to amplify this movement of cities that are committed to food. Among the suggestions that were collected, innovative trends emerge. Examples include the recognition for cities of a food competence, of a role as active producers of the food system and not only as organisers, the use of pre-emption rights as a resort for municipalities to acquire agricultural land and the consolidation of the status of public agent farmers. See a snapshot of the ideas below:

WHAT ACTIONS SHOULD BE TAKEN TO AMPLIFY THIS MOVEMENT OF CITIES THAT ARE COMMITTED TO FOOD?

The suggestions have been clustered in five categories: - Local civil servants - Funding - Regulations - Land - Networks

At the European level, the suggestions that were collected point to the same direction: it is fundamental to create a direct link between Europe and the cities that are capable of rebuilding a high-quality local agricultural fabric. Especially in terms of direct funding for public agricultural production, as for example the potential creation of "urban leader" or "inter-rural urban leader" projects.

HOW CAN EUROPE SUPPORT YOUR TERRITORY IN ITS FOOD TRANSITION?

The suggestions have been clustered in four categories: - Funding of the project - Public markets - Territories - Networks

FOOD EXCEPTION?

The last part of the Forum reflected upon a key question: what about the food exception? “We cannot buy food for community canteens like we buy pens”, says Gilles Pérole. “The free circulation of goods guaranteed by the European Market Code goes against the re-territorialisation of food and support for local agricultural transition. We need an exception to this European Code for food markets".

This hypothesis was already raised in early 2021, notably on the occasion of the BioCanteens #1 Network’s Final Event – “COP26 is already today, join the movement of European cities committed to democracy and food sovereignty”. Fast-forward to today this debate is still subject to controversy. Among the different voices that were heard during the Forum, Fabrice Riem, lawyer and Coordinator of the Lascaux Centre on Transitions, presented an interesting take on how to operationalise exceptions, without breaking the rules.

While Davide Arcadipane, from the city of Liège, described the process of dividing public tenders into multiple lots – in order to facilitate the access of school canteens to supplies coming from small local producers – Fabrice Riem pointed out how this process, which is now commonplace, represents a way to bend the Public Procurement Code without undermining it. That being said, splitting tenders into 300 to 400 lots, as practiced by the city of Dijon (FR), requires a HR capacity that small cities do not have at their disposal and, therefore, a first distinction has to be made in terms of the size of the different cities.

Still according to Fabrice Riem, "the relocation of food must not become localism, clientelism or favouritism. The European Market Code is a protection to which it is perhaps dangerous to make an exception, and also perhaps unnecessary”. If cities want to “express their purchasing power to bring about a local food system”, to use Kevin Morgan Cardiff University’s scholar own words, it would be possible to do so using current rural laws and seizing existing competencies from municipalities. At least in France, this is the way to ensure territorial anchoring, to design a call for tenders for food supply that requires a contribution to the construction of the local food system and that, ultimately, are in line with a Territorial Food Plan.

The applicant would then need to reply to questions in their bid like: when you supply this canteen, how do you contribute to the construction of the local food ecosystem? This is still a potential scenario, which should still deserves further work and that still respects the Public Procurement Code. Riem’s legal terms translated the systemic nature of food and it echoed the position that was taken by other speakers during the Forum.

For example, Léa Sturton, from the MEAD, explained how Mouans-Sartoux asks its suppliers to describe the logistical routes and transportation system in an appendix to their offer. Benoît Bitteau, Member of the European Parliament, explained that when subsidies are paid to small agroecological farms, they do not discredit the value of their food production but, on the contrary, they rather constitute the remuneration for their secondary work of caring for natural areas and preserving biodiversity.

All these ideas represented, in a practical and operational way, the principles that are outlined by of Carlo Petrini, the founder of the Slow Food movement: consuming food is much more than just eating, it is an agricultural act. Likewise, producing and buying food is not simply supplying the city's canteens, it means building a coherent local territorial food system.

--