Citizen participation is on everyone’s lips at the moment. Well, maybe not everyone’s. But many people’s. Especially on elected officials’, civil servants’ and active citizens’. It is rather common today to stumble upon press articles, radio interviews, or political programmes that mention citizen participation, and to a wider extent, participatory democracy.

Just to clarify things from the start, what do we mean when we talk about participatory democracy? Well, it’s not rocket science: participatory democracy is a form of governance in which citizens are given (and take) an active role in public decisions, and therefore in the governance of the territory they live in. It can be at local level, regional level, national level or beyond. Concretely? It means that citizens participate in political decisions and contribute to shaping public policies.

That sounds a lot like the motto “the power of the people”. But in most democracies, the participatory model is not actually the one in place. The most traditional and widely spread form of democracy is called representative democracy. We’re all familiar with the logic: citizens elect representatives who make decisions for them. This model has been in place for decades in most democracies, but it is increasingly showing signs of its limited effectiveness. To cut the story short: growing disillusionment regarding failures of policies to respond to societal needs; growing indifference leading to low voter turnout, leading to low legitimacy of elected officials; growing discontent regarding the policies that are implemented, leading to growing dissatisfaction with the current system. It’s a short version of the story, but basically, our “democracies across the globe are in crisis”, according to the Freedom in the World Report (2020). Or to put it in a more positive way… Democracy would definitely benefit from a little ‘revitalisation’.

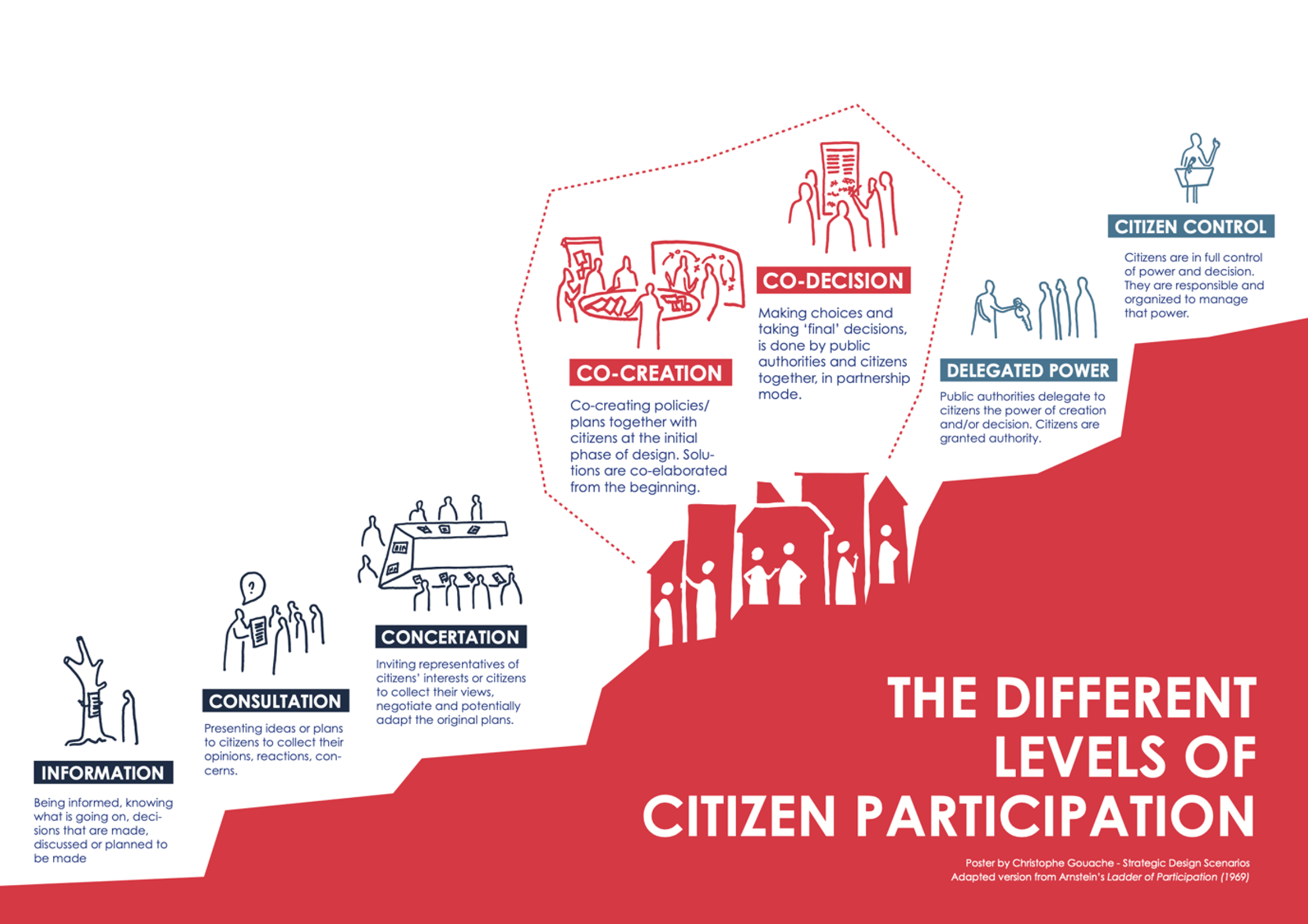

Figure: adapted version of Arnstein's ladder of participation

The good news is that a growing volume of proof tends to confirm that increasing citizen participation in policymaking is a promising way to reconcile citizens with democracy, while also potentially transforming the way policies are made in general. That means a double change. Having the reflex to give space, voice and power to citizens, and at the same time, re-thinking the policymaking process towards more open, collaborative, agile and participatory formats. Now, this conviction is largely shared throughout the URBACT community.

URBACT cities: open, collaborative, agile, participatory

If you’ve taken part in an URBACT network, whatever your role, it’s likely you’re familiar with the programme’s fundamental ingredients. Here’s a reminder: a resilient and sustainable urban policy should be integrated (systemically coherent) and participative (multi-stakeholder). Since its launch 15 years ago, URBACT has recognised the need to put participatory approaches at the core of all good policymaking process. Again, anyone who has joined the URBACT adventure will, at some point, come across the famous ‘ULG’, which stands for URBACT Local Group. What’s that? Simple: every city participating in an URBACT network needs to form its own group of people who will co-create the local strategy and action plan together with the city government. This stakeholder group shall be diverse, eclectic, mixed, and will probably include citizens, although this may depend on the topic in question.

Of course, bringing together a group of people in your policymaking process is not quite the same as installing participatory democracy across your city, but it’s a little step in the right direction. Why? Because a policy plan built with a group of citizens and stakeholders from your city is already way better than a plan built solely by civil servants. Because the more diverse the people around the table, the more diverse the perspectives on the problem you’re trying to tackle, and the richer the ideas and potential solutions proposed. So setting up an URBACT Local Group, or something similar such as a multi-stakeholder committee, neighbourhood councils, or citizen assemblies, ensures that your policies are made with the active participation of multiple voices.

Daring to experiment involving citizens

Citizens don’t bite! More local authorities should dare to approach residents, talk to them, involve them in municipal processes, ask them their views, invite them to suggest ideas and co-create solutions! It’s not forbidden, as a city authority, to engage in conversation with citizens. Yet, this communication doesn’t always come naturally (beyond the collection of complaints). Cities don’t tend to have the ‘reflex’ of involving citizens whenever they make projects, build policies, redesign public space, develop policies and plans, etc. When cities involve citizens, it’s often because they have to. By law. Not by choice. Not by conviction that it could make their projects and/or decisions better.

Obviously, I’m exaggerating a bit here. Indeed – even though it’s not yet the new normal – we’re seeing more and more cities developing participatory processes. Or at least trying to. And that’s the first fundamental step. To dare to experiment. Unless, your town or city has tried, there is very little chance that change will happen. But once you’ve done it, once you’ve worked with citizens, the added value starts showing: ideas, enthusiasm, commitment… And then, enlarging, replicating such processes will be a lot easier. So, all it takes is the initial courage to dare to experiment.

And that’s what the partner cities of the URBACT ActiveCitizens network have done. Eight small- and medium-sized cities that, with URBACT support, developed over 30 experimental Small Scale Actions (SSAs) over the past two and a half years. These eight cities are: Agen (France), Bistrita (Romania), Cento (Italy), Dinslaken (Germany), Hradec Kralove (Czech Republic), Saint-Quentin (France), Santa Maria da Feira (Portugal) and Tartu Vald (Estonia). Although some cities had slightly more experience in citizen participation than others, all have made progress. Each city produced three to seven Small Scale Actions during the course of the network. And all of these SSAs not only reinforced and re-motivated the URBACT Local Groups, but also showed civil servants that they could dare to go beyond their comfort zone and try out things they never tried before, such as engaging citizens in conversation, co-creation and co-decision, either outside, directly in public spaces or in other totally informal set-ups.

Here are concrete examples of some of these Small Scale Actions run by ActiveCitizens towns and cities:

1. Video booths

|

|

Agen (France): videomaton set in public space to record video testimonials of citizens |

Agen (France) decided to open up conversations with citizens and users in two different public squares before imagining and/or building any plan for these places. The team of Agen set up a ‘videomaton’ (video booth) tent in the middle of two squares and passers-by were invited to answer a series of questions that were recorded on video. Citizens were asked about how they perceived the square, their use of it and, of course, their wishes regarding a potential future transformation. “How would you like it to be?” This Small Scale Action is interesting for multiple reasons: first, because civil servants went out of their offices or regular meeting places and ‘put themselves on the spot’ in public space, to engage with citizens.

Second, because they used videos to collect citizens’ voices, needs and wishes: a tool that is not often seen in the administrative culture. Third, because they engaged the conversation with citizens in an exploratory way outside of any pre-formalised plan regarding these squares. There is no plan for the moment. Nothing has been decided or imagined yet. And consulting citizens without having everything already planned and finalised is rare. Cities tend to consult citizens after they’ve worked on the plan and nearly decided everything… usually not leaving much room to take citizens’ views into account.

2. Safari walks

|

|

Santa Maria da Feira (Portugal): safari-walk (exploratory walks) through the vast city green urban area for a participatory diagnosis |

Santa Maria da Feira (Portugal) and Dinslaken (Germany) organised ‘safari walks’ – variant forms of exploratory walks. In the case of Santa Maria da Feira, a large and diverse crowd of citizens took part in a long tour around the park and castle of the city to collectively diagnose the park and explore its potential future improvements. In the case of Dinslaken, a small group of young people from popular neighbourhoods did a ‘photo-safari’. Both walks used photography as a tool to enable citizens to make their own diagnosis of positive and negative aspects of public space in their city, then share and discuss it collectively. These two Small Scale Actions showed that involving citizens in urban planning projects was not only possible, but that it could also be done in dynamic and active ways, rather than classic neighbourhood meetings. This practice of organising citizen walks could become a new ‘normal’ way of involving citizens in urban planning departments, complementing other methods such as participatory mapping, vision building, or playful city modelling.

3. Mixed cultural-participatory events

|

|

Cento (Italy): the Giants' Garden is ours - participatory process embedded within a multi-social & cultural event |

Cento (Italy), among several Small Scale Actions, experimented with conducting participation outside, in the Giardino del Gigante, a public park that people had abandoned due to bad reputation. In order to gather citizens to discuss about the park, but also have them vote, decide and engage in it, the city of Cento had the smart idea of setting up a public cultural event in alliance with active local associations. Why set up a cultural event instead of a simple ‘participatory tent’? Because, very few people come to this park. The civil servants could have waited all day before catching any citizens to interact with. The ‘trick’ here was to bring music, arts, dance, circus, etc. into the park to create an event for parents and their kids, and other people from the neighbourhood.

Then, once on site, they would be invited to contribute, engage and vote. This Small Scale Action worked so well that over a dozen citizens decided that it was really a shame that this park was left abandoned. A collective of citizens decided to form right on spot: they would go on to explore the future of this ‘garden of the giants’. This solution for ‘hiding’ the participatory process within a cultural/popular event not only made people show up, but it was also a way to reach people known as ‘un-usual suspects’ – as well as the ‘usual suspects’, who regularly show up in participatory processes. Looking beyond these already active citizens is key to democracy.

4. Involving citizens in simplifying procedures

Hradec Kralove (Czech Republic) tried putting together new ‘instructions for the use of citizen committees’. Hradec Kralove has 25 ‘Local Government Committees’ (Komise místní samosprávy) composed of citizens who act as an ‘initiative and advisory body’ for the city council. Even though these committees have existed for nearly three decades, the administrative machine, its procedures, its rules, etc. still remain rather obscure for the people on these committees. How to proceed when faced with complex practical problems such as road repairs, playground refurbishment, waste problems, traffic issues, parking tensions, maintenance of greenery, complaints, investments? What are the right procedures? Who should be contacted? What are the possible solutions?

To answer these questions, the city of Hradec Kralove decided to bring together civil servants plus members of these Local Government Committees (LGCs) in order to not only clarify the procedures, but also to add a dedicated section on the city website. This new section was named ‘LGC Requirements - What to Do When I Want to Change Something’, making it easier for the LGCs to organise their activities and maintain their district.

This example is interesting both for the co-creation process – involving civil servants and citizens, rather than the city’s IT technicians alone – as well as for the way it gives citizens the tools to facilitate their engagement and ‘work’. Indeed, we often see cities that push and promote participation but don’t work on reducing or simplifying procedures. If towns and cities want to have active citizens, they must reduce or limit the administrative burden, or help people bypass it. Engaging in local actions is already quite a demanding role. So don’t overload valuable active citizens with administrative weight!

5. Participation training for municipal staff and elected representatives

Saint-Quentin (France) decided to train all the managers of the city and all its elected officials in participatory democracy and design for policies. Wait. What? We know that participation is usually encouraged by people who are already deeply convinced of its added value. But it’s not necessarily widespread within city governments, even those in the ActiveCitizens network. This is why the City of Saint-Quentin decided to make sure that no one in the city government could say “I don’t know what participation means and how it works”. And at the same time: inspire the curious ones, reinforce the convinced ones and celebrate the already active ones.

A first training session was organised for about 50 civil servants and later on the same day, training was provided for all the elected officials of the majority party, including the mayor herself. The civil servant training allowed to imagine and reflect on projects with a potential participatory dimension. It also helped trainees to realise that participation can take multiple forms… with a small group of citizens or a big crowd… over a long period of time or in a very spontaneous one-shot way… etc. For many elected officials, it was a ‘wake-up call’. When some of them reacted to the training, saying: “we know all this”, the Mayor responded: “you might know it, but we don’t do it”!

6. Ask people how they want to communicate with their local authority

Tartu Vald (Tartu Parish, Estonia) is a rural municipality of 15 000 inhabitants spread over an area of 700 km2. Due to their particularly low population density, with no major urban centre, Tartu decided to work on communication challenges. In a municipality like Tartu, where public meetings are impractical, the municipality decided to ask its citizens directly about the best ways to communicate with them. They realised it was worth adapting to people’s existing tools and habits. All too often, cities develop their own communication channel or tool without checking or evaluating its impact – such as a city app that ends up not being downloaded by residents, and then not updated by the city itself. Here in Tartu, citizens were asked about their communication preferences through an online survey. The output? Citizens highlighted three preferred information channels: Facebook groups; the municipality’s monthly magazine; and finally, occasional onsite events or gatherings.

Their survey also showed that the municipality’s participatory budget was still quite unknown to many citizens. What this Small Scale Action illustrated is the need for cities to adopt and use the same tools that citizens use on a daily basis – and to reflect on their own communication practices – the first fundamental step towards enabling fruitful citizen participation. Especially if towns and cities want to reach out and engage with people beyond the usual suspects.

7. Fun community events to build connections

|

|

Bistrita (Romania): the courtyards that bring us together. Rock the backyard! |

Bistrita (Romania) is rebuilding their relatively weak links between citizens and public authorities. A first goal was to reconnect citizens with their municipality. This meant that, rather than developing direct participatory processes, Bistrita put efforts into bringing citizens of all ages together through co-organised activities. For example, one action involved restoring and opening up historical inner courtyards for the use of all citizens, by holding a fun cultural event. This led to the creation of an actual demonstrator of a revitalised unused space, and a convivial moment of shared multi-cultural activities, including a photo exhibit, fashion show, food and wine tasting. In parallel, Bistrita also started involving school children in various activities connected with active participation: creating ‘peace banks’, Bistrita through the children’s eyes: ‘Drawing the soul of my city’ and a city treasure hunt’ to reclaim the city.

Citizen participation is no ordinary practice, but it can become one

What the ActiveCitizens city partners have demonstrated through their more than 35 Small Scale Actions is that citizen participation, even though it is not ordinary practice for all city governments, could definitely become a more regular, ‘normal’ practice of policymaking. They’ve proven that citizen participation is not only feasible through intense, expensive, time consuming, formal, institutionalised processes, but it can also be done in light, spontaneous, agile, creative ways. There is no miracle recipe for participation. But there are infinite ways for imagining participatory processes that can not only provide valuable, diverse citizen input, but also lead to fun, convivial, memorable social events.

Based on our experience with URBACT towns and cities, if there is one last word of advice for public authorities it is: As a city, opening up your processes to citizens is not enough. You need to go towards citizens, wherever they are. Go out. Go and meet the people you never meet. Because they are the precious silent voices that don't feel legitimate to speak up in our democracies. Yet.

Further information

- Do we need participatory democracy to save democracy? (Baseline study)

- ActiveCitizens YouTube channel

- ActiveCitizens URBACT webpage

- ‘Citizen participation? Hell no!’ game

- Reflections on citizen participation in Europe’s cities